Cruz, Wang use big data to track the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on college towns

Cruz, Wang use big data to track the impact of the pandemic on college towns

The COVID-19 pandemic wreaked havoc on our lives this year, a fact that is especially salient to the students and faculty who abruptly shifted to online learning in March—and the parents and community members around them who also have been affected by the departure from normal college life.

Distinguished Professor Isabel Cruz and Zhu (Ellen) Wang, a doctoral student in the Advances in Data, Visual, and Information Science Research Laboratory (ADVIS) lab, which Cruz directs, wanted to know what the people in college towns, from students to business owners, were discussing and sharing about these changes during the spring and fall.

“We wanted to contribute our experience in analytics and big data to the study of the COVID-19 pandemic,” Cruz said. “When thinking about the impact of COVID-19, we remembered how difficult it was to adapt overnight to online learning.”

Cruz and Wang approximated the sentiment of U.S. colleges and universities and the communities around them by computer-analyzing posts on Twitter. They harvested tweets by time and location to capture what people were saying online as confirmed COVID-19 cases spread throughout campuses. They conducted computerized content and sentiment analysis on these posts to evaluate the topics of people’s tweets and the specific thoughts they expressed.

Twitter has become a crucial tool in determining how people find and disseminate health information in an urban environment, Cruz said. It’s a big change: as recently as 15 years ago, community health centers and healthcare providers still communicated information about topics such as flu cases via fax.

“Nowadays, researchers and healthcare entities rely on Twitter to detect flu trends and conduct disease surveillance, especially on geotagged tweets,” Cruz said.

Using a dataset of more than 6 billion COVID-19-related geotagged tweets, Cruz and Wang mapped tweets and correlated that information with confirmed cases of COVID-19 cases in college towns. They studied the content of those tweets, tracking keywords and looking for expressions of negative and positive emotions to determine the overall sentiment of the tweet.

Their research showed two peaks of negative sentiment over the time period they studied: one at the beginning of the pandemic, as many schools started to cancel their classes or move them online, and another even larger peak in mid-July, when many states were reopening but plans for higher education was unclear—and when students and faculty may not have felt safe returning to campuses.

An area of ambiguity in the research, which Cruz and Wang may explore in a future study, is how to interpret the use of the words “positive” and “negative” in tweets. In most situations, the word positive correlates to a positive emotion, and negative to a negative emotion. With COVID-19, the words may have an opposite implication: a negative test result is good news, and the word positive can be used to indicate one has contracted the disease.

Cruz and Wang found that one of the biggest topics of conversation in many states was not about the disease itself, but rather its financial side effects.

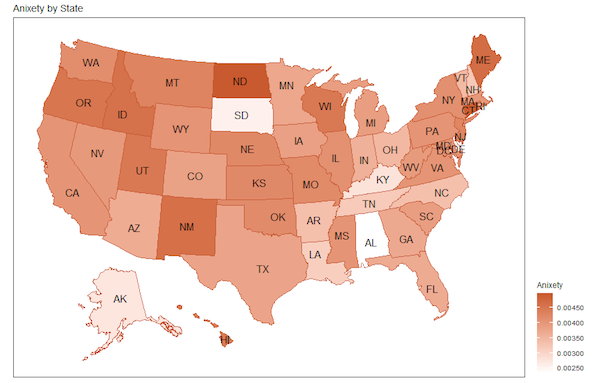

“Many of the students were talking about funding and student loans,” Wang said. “They expressed a lot of stress and anxiety in this area, but it was very different in different states.”

The duo presented their paper, Analysis of the Impact of COVID-19 on Education Based on Geotagged Twitter, in November, at the 1st ACM SIGSPATIAL International Workshop on Modeling and Understanding the Spread of COVID-19. They may use this work as a baseline for future studies as the pandemic continues.